No products in the cart.

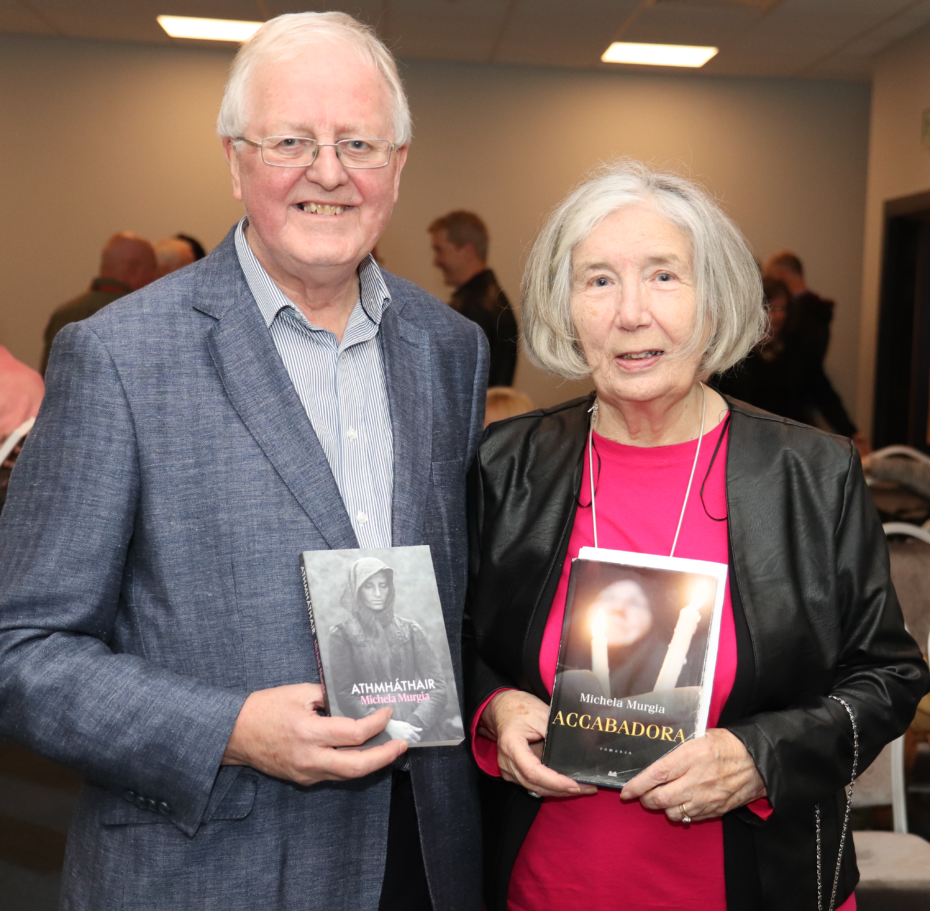

Launch of ‘Athmáthair’ at Oireachtas na Gaeilge – translation by Máire Nic Mhaoláin of the book ‘Accabadora’

The well known writer Antain mac Lochlainn launched Athmháthair by Michela Murgia at Oireachtas na Samhna on Saturday 4th November

Eoghan Mac Giolla Bhríde said a few words before the launch

“When a book like this comes to a publisher it’s the breath of life for us in reality, as a company it’s what keeps us going, and we are so grateful to Máire for sending us this book. It is a privilege for us to be able to bring literature like this, world literature, into the world of Irish, and to have that chance because Máire had faith in us, a small company from Gaoth Dobhair, we are very grateful to her indeed.

Antain Mac Lochlainn was introduced and he gave an erudite talk that kept everyone’s interest to the end. Describing the craft of translation, the challenges of the work at times and the benefits that come with doing it well. The full speech given by Antain is given below and we are very grateful to Antain for making it available to us.

Antain Mac Lochlainn’s talk at the launch of Athmháthair by Michela Murgia, Saturday 4th November at Oireachtas na Samhna in Killarney

When I started to learn Irish, I subscribed to the magazine An tUltach. I used to spend two days trying to make sense of the articles, although I didn’t always succeed. But I remember one article entitled ‘An Tan a d’Aistrigh’ by someone called Máire Mic Maoláin. Today, I know there is a clever pun in that title. In many of the old manuscripts, that is the title given to the famous poem ‘Is Fada Liom Oíche Fír-Fliuch’ by Aogán Ó Rathaille, a poem he composed when ‘an tan’ (or the time) he moved to live west of Dubhneach. I didn’t know that at the time. I saw An Tan a d’Aistrigh and started reading, thinking it had something to do with the War of Independence. But it wasn’t. This was Máire Nic Maoláin discussing matters of translation.

Having Italian in front of you and your challenge is to remember Irish words that have the same meaning. That’s the bottom line of translation, in my opinion – sort of ‘bilingual word processing.’ But this was not what Máire Nic Maoláin was saying. She was talking about the craft of translation, the choices that have to be made, the things that make translators tired when they are not careful. It was the first time that it dawned on me that translation is creative work and that it is a profession. I did what you would expect for an article about translation matters that I didn’t understand fully – I translated it.

The years went by and I started to read Irish books. I didn’t care whether they were original books or translated works as long as they were in Irish. In the late eighties I encountered Máire Nic Mauláin again, when I read Dialann Seansagairt, a translation she made of a collection of essays by a rural priest in the Umbria region of Italy. Now, I can say that I don’t usually read religious books, but I am glad I read that one. It has elegant prose, and a kindly and gentle outlook that I loved. Those who do not read translations into Irish, are denying themselves a great pleasure: the pleasure of reading a book that you would never read except for it was made available in Irish. I think of that gorgeous English word serendipity. The Irish for that, according to the new dictionary, is ‘good fate’. Yes, it was good fate for me to come across that book.

I don’t speak Italian to be able to do a comparative analysis of the text, but I was learning about the translation anyway. I realized, after reading it, that there is a lot of trust involved in the relationship between the reader and the translated work. One small slip, a clumsy speech, a misplaced sentence, is enough to undermine the reader’s confidence and bring all the good work to nothing. The translation is High-wire act, as stated in this verse:

Many critics, few defenders

Translators have but two regrets;

When they hit, no one remembers,

When they miss, no one forgets.

It seemed to me, in the case of Máire Nic Maoláin, that her aim was spot on, and that I could trust her. This is someone who understands her profession and practice, as opposed to a hobby. Shortly after reading Dialann Seansagairt, I read an English translation by D.H. Lawrence of another Italian work, Novelle Rusticane by Giovanni Verga, published under the title The Little Novels of Sicily. It appears that Lawrence had pretty good Italian, but what does ‘pretty good’ mean in the context of translation? Something that people used to say if they were asked about their ability to speak Irish, ‘Oh, I’ve got some work to do’. Lawrence may have ‘done some Italian’ while in the shop or in the pub but when he got down to translating, he was relying heavily on dictionaries. ‘It was a pity I was depending on dictionaries.’ Both a star of knowledge and a pit of mud are the dictionaries. Back in the fifties, a man named Giovanni Cecchetti published a long list of Lawrence’s mistakes, when he took the meaning of an Italian word or phrase. Another critic, Iain Halliday, said: ‘The story of how Lawrence translated (Verga) is an object lesson in how not to approach literary translation.’I didn’t know that at the time but, while I was reading, I said to myself, ‘I don’t know if I trust D.H. This Lawrence, as a translator, as a guide between the two languages.’ For all his fame, I could see he couldn’t hold a candle to Máire Nic Mhaoláin

Here’s another Italian work that Máire has made available to Irish readers: Athmáthair. It is noteworthy that the direction of the translation itself for the most part come from English and if not English, French. In Máire’s translated work so far, it’s nice how Máire has kept a small window open for us on Italian life. The original book Accabadora by Michela Murgiahas won a long list of literary prizes in Italy and other European countries. Therefore, it is a major work of art from Europe that Máire and Éabhlóid have made available to us. That’s no small thing. Of course, the people of Ireland are not unaware of the merits of the book, for the English translation was longlisted for the Dublin Literary Prize in 2013. Be that as it may, I must admit that it is unlikely I would have read it but Máire made it available in Irish. Another good decision.

The events of this story take place in a poor community in a Sardinian village during the fifties of the past century. A historical novel, then, but not of ancient history. Perhaps we should not call such a ‘near-historical novel’. In connection with Athmháthair, periods of time have collapsed into each other in a mysterious way. There are passages where you would think that the customs of the seventeenth century are being discussed, until it is mentioned that the people are wearing jeans and that they are watching television. There is a lot of old and new in it – which is appropriate for a work with eternal themes of ‘death and life’.

In some ways, Irish language readers will be experienced in the life depicted in Athmáthair. The hand to the mouth. The small allotments and disputes about where exactly the boundary wall is – neighbours falling out with each other because of a meter of land. Black shawls. The wake house and the mourning of the dead. The Christian faith intermingled with the superstitions of country heathers. A priest, if you don’t mind, is referred to in this line: He made a sign that was halfway between the truth of the cross and the sign against the damaged eyes.That’s how the people in this book live: halfway between truth of the cross and the evil eye.

The gossip and small mindedness is there as well – sort of like Valley of the Squinting Finestre. Even the language tensions are there, the difference between the school Italian and the Sardinian language of the home. There’s a scene or two that would remind you of Nuair a Bhí Mé Óg, with poor Séamus Ó Grianna grappling with his English lessons.

There is a secret at the heart of this novel. Because of that, there are things I can’t comment on, for fear of spoiling the story for you. I would advise you, after buying the book, not to read reviews or go online trying to find out what accabadora means. Read the book directly. There is a lot I cannot say, but I can count the merits of the book. The first thing I would mention is the smooth pace of the narrative. It often seems to me that writers are under pressure to start their story with a devastatingly explosive start – a big explosive start, like in thrillers. What Murgia has done is to place a series of vignettes in the first chapters, which give us an insight into the life of the Soreni people, the area where the story is set. Those chapters are purely elegant. We get to know the main characters during it, in such a way that once the casualties and tragedies that happen later are more deeply affecting to us.

There is humour in it, a humour that is closely related to the disputes and the struggles in Cré na Cille. It’s also a subtle comedy. You would miss a lot of it if you were in too much of a hurry. Like this, commenting on an marriage engagement that was made: ‘The day that Bonacatta married, two terrible things happened, apart from the marriage itself.’ A humour that is squeezed out of poverty. This is part of a conversation between two people who meet each other in the street – a question and answer, so to speak.

Question: “An who is the beautiful young girl?”

Answer: “The last one”

It’s a very narrow life the characters have, a life lived according to the strict rules of status: between young and old, healthy and prosperous, male and female. If you come into disrepute for any reason, you are done for as it is a culture of respect that prevails and there is no greater dishonour than lack of respect. These are the thoughts of one father, after his son committed a misdemeanor. He understands that this will give the whole family a bad name.

Soreni had no worse joke than being a fool. Or if wisdom and strength and wisdom would lead to victory in a fair battle, the fool had no worse enemy than himself, or his foolishness would leave him equally dangerous to his friends and enemies. The downside was that no respect could be attached to the name of the fool in either case, and respect was a great asset in a place where there was not much else at the time.

It seems that it is up to the public to judge what constitutes a ‘fool’ – the odd bird, perhaps, the person who stands out from the crowd. ‘There are things that are done and things that are not done,’ the main character Maria says to herself, ‘and the things that are done, that’s how they are done.’

There are degrees of status within the family itself. Maria is the fourth child in the family and it is made very clear to her that she is fourth in every aspect of that family’s life.

‘Her mother… was fascinated by the numbering system in one form or another, and this only gave Maria the opportunity to see herself in order alongside her sisters, always referring to her in the same formula – clean out, ‘Number Four.’

And, of course, she is a girl and of little value. So little that her mother lets another woman take her and raise her when she has no children of her own. This woman’s name is Bonaria, the ‘Athmháthair’ of the title. She was left a widow after her husband was killed in the first war. Whatever heroism he achieved for himself, it was dearly bought. ‘Heroism’ is a heavy word in the context of this book. This is how Bonaria himself understands the story: ‘Bonaria had seen enough of life to understand that the word ‘hero’ is the masculine version of the feminine word ‘widow.’

Above all else though, Athmháthair is a tragedy. The characters destroy their own lives with selfishness, revenge and misunderstandings, just as humans tend to do. Two-thirds of the suffering is visited on women. The author Michela Murgia was an active feminist, but there is no trace of causality or ideology in the story. Humanity is there from beginning to end. Empathy for the priest who was always trying to hide his big stomach under his ecclesiastical coat. Understanding for the young men who are being told that they must always stand up for themselves, even if they are confused. Even the spoiled rich boy, who would have been the object of ridicule by other authors, it is revealed to us the inner heartfelt inner turmoil he feels. The author is a big-hearted person: a feminist, a Christian, someone who spent a spell teaching theology and another spell as a power station manager. Such life experience!

Michela Murgia’s death this year is a great loss. She died in August to be precise, at only fifty years old. Congratulations, Máire and thanks to Éabhlóid, who have put a stone in the pile with this beautiful Irish version, Athmáthair. The best act of respect we could do is to buy it, read it and spread its fame.

Eoghan thanked all the people who had worked on the book, Liam Mac Mathúna the copy editor, Caomhán Ó Scolaí who did the layout and design and Clár na Leabhar Gaeilge who provided funding.

The book Áthmháthair is available in bookshops and here on this website.